Making a documentary is like surfing. I imagine. I don’t surf. But there is a similar combination of applying skill and technique to elements that are outside your control. The ‘waves’ in this metaphor are the vagaries of life itself. You follow stories and people that have a likelihood of leading to actuality-driven scenes – a porn star failing to get wood on set, a confrontation provoked by a homophobic cult. On occasion you arrive at the beach with your board, having read reports of monster waves, only to find the sea as calm as a millpond. You keep coming back and usually, eventually, you get what you need. Or sometimes you don’t. And then on occasion the unexpected happens, and your contributors are accused of a bizarre sexual assault at a swingers’ party in Ilford.

The Hamiltons had been among the names we approached without thinking that hard about whether or not we really wanted to film with them. At that time they were fixtures of a low-wattage celebrity circuit. Neil Hamilton, a former minister of arch-Thatcherite views, had been forced out of politics for allegedly taking bribes in return for asking questions in parliament. He’d become a poster boy for what was termed Tory sleaze and had lost his seat in a high-profile election. His wife, Christine, had featured prominently in the coverage. Whereas Neil seemed mild and slightly robotic, she came across as fierce. She had helmet-like hair that looked as though it had been glued in place and when her dander was up, which was not infrequent, a scary basilisk gaze.

The accusation that Neil had taken bribes came from the owner of Harrods, Mohamed Al-Fayed. Fayed said he’d given Neil money in brown envelopes. Neil disputed this and brought a libel suit against the Guardian. He lost the suit, and a subsequent appeal, to the tune of several million pounds, finally declaring himself bankrupt a few months before we commenced filming.

At the time we approached, they were attempting to make lemonade from the lemons of their disgrace, plying their trade as ‘professional objects of curiosity’ – Neil’s term. Any money Neil earned was siphoned off to pay his legal debts; Christine wasn’t technically bankrupt so she could keep her fees for media appearances.

And there had been one or two suggestions of non-mainstream romantic practices, including an Oxford student who’d gone public to say that, during a speaking engagement at the university, Christine had snogged him.

They weren’t busy. As documentary material, it wasn’t a lot to go on. Still, they made an intriguing couple – there was something about them, his otherworldly quality and her intensity – and we weren’t exactly spoiled for options.

I arrived one summer morning, getting lost on the stairs leading to the top-floor flat in a modern block in Battersea. This was their London pied-à-terre. They also had a large rambling house in Cheshire but they were in the process of selling that to pay their legal bills. As was our custom in those days, we started with a tour of the place, chatting as we went. The Hamiltons were friendly, forthcoming, conscious of the need to perform for the camera.

The flat, which overlooked Battersea Park, was cosy and piled with knick-knacks and books. A mug in the kitchen said, ‘I am a naughty forty’. There were prints and portraits on the walls, and old political cartoons – several of them referring to a libel suit Neil had brought against the BBC. In 1984, a BBC Panorama documentary entitled ‘Maggie’s Militant Tendency’ had alleged that Neil was part of a cabal of right-wing extremists that had infiltrated the Conservative Party – he’d sued and the BBC had settled, paying him £50,000 in damages.

Not having much to go on, other than the allegations of Neil’s corruption and Christine’s snog, I was nibbling away at the idea that they might be sexual boundary-pushers in some vague way. We went into the bathroom, which was also cluttered with books and tiles with Willie Rushton caricatures of fat naked ladies running around. Not quite knowing what I meant by it, I asked Neil if he and Christine were ‘saucy’. His reply became the opening exchange of the finished documentary. In words reeking of prophetic irony, he said, ‘No, not at all. It’s been a permanent source of regret that the one thing I’ve never been involved in is a sex scandal.’

A few days went by. We filmed a sequence of Christine getting her hair done at a salon in Mayfair called Michael John, and another of me and Neil working out together on a ‘trim trail’ in Battersea Park. In their front room we watched a pilot of a TV show they had appeared in entitled Posh Nosh. A strange cookery-cum-travel format, it showed the Hamiltons descending upon a big unruly family in a council house. Christine whipped up a gourmet meal while Neil did duty as a butler.

We filmed a trip down to the South Coast somewhere to meet a friend and supporter of Neil’s, an influential academic called Lord Ralph Harris or Ralph, Lord Harris – I’m honestly not sure how you write that. His name was Ralph and he was a Lord. An economist and disciple of Milton Friedman, Lord Harris had a comical tweedy air about him. He seemed a man born out of time – he should have been stepping out of a flying machine, smoking a pipe. My chief recollection from the visit was of Lord Harris leaning in and confiding his sense of confusion that his academic protégé and his wife had been reduced to going on a Channel 4 programme – The Harry Hill Show, as I knew it to be – ‘dressed up as badgers’. It was one of a handful of times in my filming career when I’ve laughed involuntarily.

Then their diary went a bit quiet for a few weeks. It wasn’t quite clear what else there was to do with the Hamiltons and there was a dawning possibility that they were so unbusy that we might need to let the project slip gently away.

At dinner one evening – it may even have been after the Lord Harris visit – Neil and Christine made an elliptical reference to a new commitment, something in the diary that was causing them a lot of stress and anxiety. They couldn’t tell me what it was, they said. I was fairly sure it didn’t involve dressing up as badgers. But off camera – possibly off-the-record – they told Will my director a little more. He in turn told our executive producer David, and there followed a weird few days when they knew what ‘the thing’ was and were in a position to tell me more while I was keen not to know. I was a bit more of a purist in those days and I liked the idea of being informed about ‘the thing’ – whatever it was – for real on camera by Neil and Christine themselves.

Still, I couldn’t help wondering.

‘Is it big?’ I asked.

‘It isn’t Cheggers’ Bedroom, put it that way,’ David said.

‘Will it have implications for the documentary?’

‘Yes.’

‘Is it something we can follow?’

‘Yes.’

‘Well, that’s good, because fuck knows we need something.’

‘Yeah, quite,’ Will said.

‘Is it animal, vegetable or mineral?’ I asked.

‘Look, what harm can it do for you to know?’ David said.

‘Well, I’ll have to act.’

‘All you have to do is say “shit!” or something like that.’

‘It’s just more fun like this,’ I said. ‘It’s tantalizing.’

The result was, on 10 August 2001, I stood on a road near Harley Street and was blindsided by Neil telling me that he and Christine were about to drive, with their lawyer, to a police station in Barkingside, where they would be arrested, by arrangement, on an accusation of indecent sexual assault.

A woman, about whom they knew little, had alleged that Neil and Christine had raped her at a swingers’ party in Ilford in Essex. As unlikely as it sounded, the police were taking the accusation seriously. They’d had three months to check the information. (The Met would later claim that they had twice invited the Hamiltons to provide alibis, which would have forestalled the arrest. The Hamiltons deny this.)

The drive to Barkingside involved a long circuitous car ride through the capillaries of east London’s traffic system. We were in the company of the Hamiltons’ lawyer Michael Coleman, in his car, license plate: ‘1LAW’. Despite the Hamiltons’ evident stress and anxiety, Coleman was having trouble hiding his own relish for the impending battle with the police and media. ‘This hasn’t got anything to do with law,’ he said. ‘Principally what this is about is a psychology game.’ He referred to the Hamiltons as a mere ‘ball’ in a grudge match between himself and the authorities. Christine, in one of her stock phrases of disapproval, said, ‘Well, thank you very much.’

The strange sense of the stakes involved gave the car ride a surreal quality. I wondered how long they’d known about the allegation. Whether they had or hadn’t done it, both options struck me as horrendous. The heightened reality of the occasion meant I thought I could feel them both improvising the drama in different keys: jolly and serious and sad. Neil kept making off-colour jokes. They had been at Lord Longford’s funeral earlier in the day.

‘Perhaps they’ll be accusing us of necrophilia next,’ Neil said.

‘Neil, will you stop,’ Christine said.

At the police station we split up. Will and I waited outside while the Hamiltons went into the station to be interviewed. For a while all was quiet. I wondered whether the story would be kept hush-hush. Then, slowly, a few reporters appeared, followed by a few more, until a full orchestra of camera crews and paparazzi were arrayed, as though tuning up for a big performance.

A few hours after they’d gone in, the Hamiltons emerged. Michael Coleman gave a statement.

‘It’s said that Mr and Mrs Hamilton were in a flat when a young woman was raped,’ he said. ‘It’s also said that Mr Hamilton was masturbating onto her whilst another man, as yet unidentified by the police, was also masturbating onto her and Mrs Hamilton was squatting on her face.’

As he said this, Neil and Christine flanked him, both looking impassive.

‘I take it, Mr Hamilton, you deny this?’ asked one reporter.

‘We deny this absolutely categorically,’ Neil said.

Christine put her arm around Neil. ‘I’m very happy to put my arm around my husband,’ she said. ‘The whole thing is an absolutely monstrous fabrication and a lie . . . You can all get your photos.’

After the press conference, surrounded by a scrum of press, we climbed back into Michael Coleman’s car. Christine put the car window down, and I leaned back so the photographers could get a couple more shots of the unhappy couple. Then we drove off.

In his statement, Michael Coleman had said that during their interviews the police had brought up the name Max Clifford, the celebrity publicist famous for brokering kiss-and-tell stories with the tabloids.

‘The whole thing’s an absolute nightmare,’ Christine said. ‘As we thought, Max Clifford! Why would the police ask us about Max Clifford? Course he’s behind it. He’s got what he wanted. Whatever happens now, if we never hear another thing about it, we’ll be all over the papers . . . Six policemen are combing our house! Opening every door, every cupboard. They’re searching in all my clothes for a blue dress . . . It’s absolutely monstrous.’

She became weepy. Then, noticing Neil was on the phone, she said, ‘If that’s the Guardian, just put it down, darling. Don’t even talk to them!’

‘Sorry, I can’t talk any more now,’ Neil said into the phone.

‘The only identifying characteristic she could come up with was a blue dress?’ I asked.

‘She doesn’t even know if I’m circumcised or not,’ Neil said.

‘Oh, for Christ’s sake!’ Christine said and put her hand over her face.

‘We asked that question of the police,’ Neil said. ‘Needless to say they hadn’t thought to ask it.’

‘Do you know, at one stage they were going to lock us each in a cell?’ Christine said. ‘Can you believe it? Just because Max Clifford and some tart have invented this allegation!’ She started crying again. ‘We’ve had enough to put up with in our lives without all these lies.’

Trying to be helpful, Michael Coleman said, ‘Take it in your stride.’

‘Oh Michael, it’s just a game for you. It’s my life. It’s my reputation. What a ridiculous thing to say. “Take it in your stride.” ’

Her voice was quavering and she covered her face again as Neil stroked her forearm with the tips of his fingers in a stiff up-and-down gesture.

Back at Michael Coleman’s house there were drinks. Christine had several fortifying glasses of wine. Then the four of us – Neil and Christine, Will and me – continued on to the Battersea flat. Neil was driving. Christine was feeling the effects of the alcohol.

‘I think we need to have something to eat,’ Neil said. ‘I hesitate to say you need to get something inside you.’

‘Oh, for God’s sake,’ Christine said. ‘Will, if you broadcast that I shall come round personally and stab you.’

At their flat a gauntlet of press – six or seven camera people with top lights on – swivelled in unison without saying a word. They were like alien creatures or robots. Upstairs we watched the news of the arrest on television. I had a glass of red wine to alleviate the stress and strangeness of the day’s events. Then I had a few more. By now we’d been joined by a journalist from the Mail on Sunday called Paul Henderson, who declined to go on camera and lurked in the kitchen. I had the impression he was ‘babysitting’ the Hamiltons, with a view to landing their exclusive story.

‘Paul’s on side,’ Christine said. ‘Paul’s helped us a lot.’

I had a whispered conversation with Paul outside the kitchen. I was – to use the technical word – slazzered at this point and feeling magnanimous.

‘It just seems so unlikely,’ I said. ‘I mean, I really don’t think they did it. It would take such brazenness on their part if they had done it to then go and invite our camera in. I mean, who is capable of that kind of sangfroid?’

‘Well,’ Paul said, rolling his eyes, ‘anything’s possible. I’ve been doing this job so many years, seen so much. I’ll tell you, nothing surprises me any more. Nothing.’

A little later I went to the loo. Will came in to have a covert conference and then, possibly feeling a little emotional himself, he did an impression of Neil Hamilton masturbating onto someone at a swingers’ party.

It being August, news was in short supply. The allegations against the Hamiltons were a sensation. The story was across all the news channels and in the tabloids, quickly mutating into a meta-story about the ludicrousness of the ‘media circus’ itself. This struck me as a little unfair: if anyone was responsible for turning the story into a media circus, it was surely the media.

My feelings at this point were complicated. I suppose I should have felt grateful that the Hamiltons had allowed us to continue filming, though I was also conscious that it was potentially helpful to their case to be seen cooperating with press. It could be taken as showing that they had nothing to hide. At the same time, many people regarded the Hamiltons’ appetite for coverage as a further example of their supposed shamelessness and another count against them. But mainly I was confused by the turn of events and bothered by the strangeness of finding myself now a part of the story (as I increasingly was). In almost all the coverage there was a photo of me with the Hamiltons as we drove from the police station, with a reference to me as ‘wacky TV personality’ Louis Theroux, the fact of us making a documentary prefaced with the phrase ‘in a bizarre twist’.

Among my friends and colleagues the prevailing attitude seemed to be that I should feel lucky to land such a scoop, a few going so far as to suggest I’d been part of making up the allegations to help our story along (as if). But I was also struggling with a sense of self exposure. One of my impulses in making documentaries had always been an urge for invisibility and escape. This time my escape route had led out into a spotlight on the main stage.

I was also surprised at how many people thought the Hamiltons actually had taken part in the rape. It was fairly clear to me early on that the case against them didn’t add up. Whether or not they went to swingers’ parties, they didn’t go to them in small flats in Ilford. And in fact, within a few days of the arrest Neil had found several receipts placing him at Waitrose and witnesses to support his contention that they’d been hosting a dinner party on the night in question.

Still, there was no question of not continuing, and so, two days after the arrest, after a day off from filming, Neil, Christine, Will and I drove up to the Hamiltons’ Cheshire pile. There we stayed for three days while the media camped outside. It was a little like The Masque of the Red Death. We drank and talked and Will filmed while a contagion of irrationality rampaged outside.

Forced together with them in the surreal circumstances of the media siege, and having lost my bearings as to what exactly my journalistic role was, I found myself enjoying the company of the Hamiltons in a more or less straightforward way. Neil’s robot-like exterior belied a droll sense of humour. I would slip into my own robot-like mode, and we would compare notes about subjects we were both interested in: the American anarcho-capitalist philosopher Robert Nozick, the historian Thomas Carlyle, and Nietzsche (of whom Neil was a great fan and had done a line drawing which hung framed on the wall). Given the accusations made in the Panorama programme, I was on the lookout for evidence of far-right leanings, noting the many books by Enoch Powell. Neil would do impersonations of the famous ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech in Black Country tones. ‘Like the Roman, I seem to see the River Tiber foaming with much blood.’ He was knowledgeable about minstrelsy and enjoyed talking about various dubious blackface vaudevillians of the belle époque. In a sublimated attempt to derail Sacha Baron Cohen’s then-flourishing career, I encouraged Neil to write a piece about him and whether he could be said to occupy a place in the minstrel tradition for the Daily Mail.

Christine was up and down – stern and fierce one minute, dissolving into tears the next, which to be fair, seems a reasonable reaction when accused of rape. ‘I’m having a bit of a dip,’ she’d say. In her up moments, she was reminiscent of dominatrices I’ve met, especially when she’d had a drink. If you interrupted her train of thought she’d snap ‘Shut up!’ or slap your leg.

In many respects, their match-up was of the classic Mars-and-Venus variety: him, stoical and underplayed; her, buffeted by emotional turbulence.

I began wondering why anyone might possibly fixate on the Hamiltons as the object of fantasies. I recalled that, before any of the rape allegations, a colleague at work had said, ‘There’s something about that couple’, implying by her tone that she thought they might have unusual sexual interests. The first night in Cheshire, over a dinner – for which Christine made the same Bloody Mary jelly as she had for the alibi-providing party – I put it to them that people felt there was a mystery at the heart of their relationship.

‘For some reason you have a hold over the public imagination,’ I said. ‘And there is a sexual dimension to it.’

‘Why do you think that?’ Neil asked.

‘When I mention “the Hamiltons” people say, “Oh yes, there’s something funny about that couple.” ’

‘I simply don’t believe it,’ Christine said. ‘Tell me anybody who’s said that.’

‘I think there’s a belief that there’s a secret at the heart of your relationship that no one knows,’ I continued.

‘I don’t know what you’re talking about,’ Neil said.

‘May I ask a sensitive question? Are you sexually quite normal?’

‘Yes, completely, a hundred per cent normal,’ Christine replied. ‘We have no deviations. Absolutely nothing. Very happy with each other. We have no problems, we’ve never had any problems. A great life, thank you very much.’

Meanwhile the media frenzy continued, hitting ever higher levels of absurdity. On the first morning in Cheshire, a man turned up, a one-time TV reporter who was now a truck driver and the creator of the website neilhamiltonisinnocent.com. He had brought a banner with the website name on it and was intent on using it to give the website a plug on national TV – he persuaded Neil that he and Christine should carry it while marching out to the waiting reporters in a kind of procession. I counselled against this. I was aware that – as a journalist myself and supposed disinterested party – it wasn’t really my place to advise but I couldn’t help myself. For a while it turned farcical, with Christine freaking out that the banner was lying crumpled out on the drive in view of the cameras. In the end, they made their statement with no banner. In the live coverage Will and I were just visible lurking in the background, like a couple of shabby stagehands who have strayed into shot.

That night, after supper, I was reclining in a sofa when Christine came and sat next to me. Neil was out of the room. She began stroking my cheek.

‘You haven’t shaved,’ she said.

She must have been aware Will was filming and I wondered if she was doing it for the camera.

‘You do like to flirt, don’t you?’ I said.

‘Who doesn’t like to flirt? I mean, if you can’t have a little fun, come on!’

I felt a familiar sort of doubling: immersed in a weird situation but aware that it was probably helpful for the documentary. I hope I am not being unkind to Christine when I saw it was a little reminiscent of being hazed by the wrestlers at the Powerplant.

Neil returned from the kitchen and, noticing us, did a comical double-take.

Later, after a couple more drinks, Neil decided he should go up the driveway and deliver a statement to the waiting cameras. Will and I followed him. No one was there.

‘I’ve got a statement,’ Neil shouted into the darkness. ‘I love Will Yapp!’

After a few days the story ebbed away. The accuser, who went by Nadine Milroy-Sloan but whose real name was Emily Checksfield, turned out to be a troubled young woman from Grimsby. A fantasist, she had been visiting sex chat sites and became convinced that two of the people she conversed with – ‘Lord and Lady Hamilton’ – were Neil and Christine. Smelling a financial opportunity, she’d visited Max Clifford, who’d told her she could sell a sex story about the Hamiltons for six figures but would need proof. In short order, she arranged a visit with her online correspondent – a pensioner in Essex called Barry Lehaney. It was on an evidence-gathering trip to see Barry Lehaney that she said the sex party and the rape took place.

Lehaney’s account of the visit differed markedly from Milroy-Sloan’s. In his version he’d picked her up in his Ford Granada and taken her on a tour of London sites. They’d bought some food and wine at Tesco’s then watched Trigger Happy TV at his flat. He’d offered her the sofa but she’d asked to sleep in bed with him. The following morning, unprompted, she’d masturbated him.

The detail that strikes me now is that Milroy-Sloan complained of feeling woozy after drinking a glass of red wine brought to her by Lehaney. Police found a strip of Rohypnol at Lehaney’s flat, though Lehaney claimed it was planted. In any case, having made up the tale of the group rape, Milroy-Sloane’s allegation of being drugged was thereafter unlikely to be believed.

On 13 July, Nadine Milroy-Sloan was convicted of perverting the course of justice and given three years. The judge commented: ‘It’s becoming all too easy for people to sell fake allegations about well-known people to the press, and the courts have to deal with it firmly.’

When Louis Met The Hamiltons marked a kind of weird high-water mark of my professional fortunes. Other people may have different barometers, but for me you are too famous when your image and likeness are thrust into the consciousness of people who don’t like you. There is a lot to be said for being avoidable. But for a couple of months, for those who read papers and watch TV, I was hard to miss. One night at home, stoned, I was watching a dating show. The young woman said she didn’t want to go on another date with the specky bloke. ‘He looks too much like Louis Theroux,’ she said. Had I become a byword for a certain kind of unattractive man with glasses?

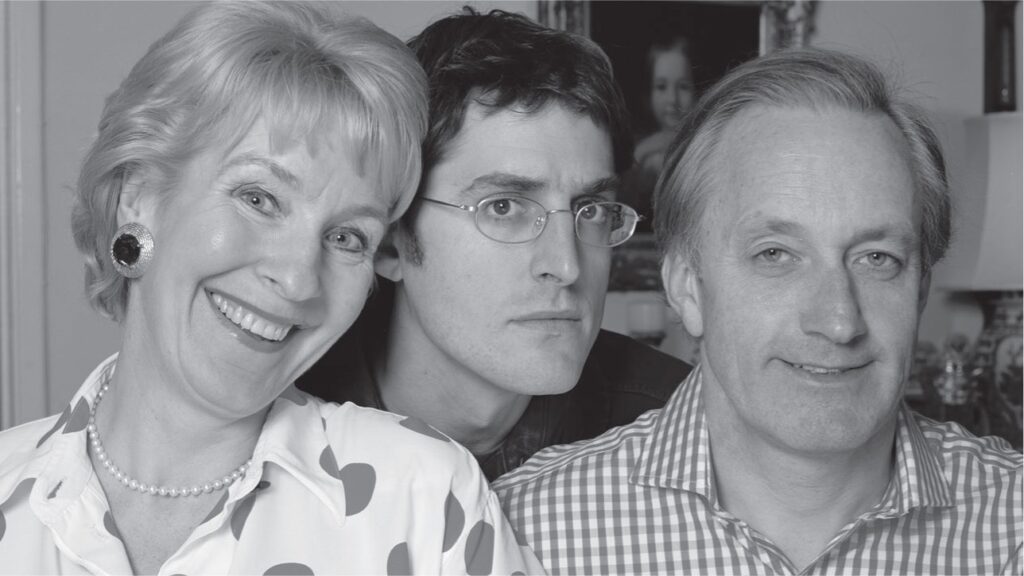

With Neil and Christine Hamilton.

What felt especially untoward was to have achieved success with a programme that hinged on nothing I’d done. A bizarre piece of happenstance – a lightning strike of misfortune that zapped Neil and Christine Hamilton – led to events that we were lucky enough to be around to document. All the excitement it created – at the BBC, among my exec and his higher-ups – felt to me like a prison sentence. David was in ecstasies over the success of the show. Nearly five million viewers. Stories in all the papers. But it worried me since there was almost nothing to be learned from making the documentary in terms of process – you can’t choose your subjects based on whether they might be accused of rape by a deluded young woman. Meanwhile, I had an unfamiliar sensation of being in demand. Offers of ‘at home with’ photo features in magazines. GQ invited me to be their TV personality of the year, which I politely declined. In Edinburgh for the TV festival, the channel controller of BBC1, Lorraine Heggessey, fell into step beside me in the lobby of the Caledonian Hotel.

‘So tell me about the Hamiltons,’ she said. ‘I think we might want that for One.’

All the attention and the sense of approval had a paradoxical effect, making me wonder about before. Did people not like the shows then? I began feeling morose, sensing that I was completely out of sync with what everyone else seemed to think I should want. My appetite for the sort of programmes I was doing, already in decline, dipped precipitously around this time. But I was a success, creating impact, and so there was no getting off the bus. And besides I had a ton more shows to make, and no sense of how I was supposed to make them.